Lots of openings, fewer raises — The current U.S. labor market puzzle

For the last several years, the plunging unemployment rate has led many economists to call for accelerating wage inflation in what should be a tightening labor market.

Economists are still calling for accelerating wage inflation as actual wage inflation is only picking up modestly.

In April, average hourly earnings rose 2.6% over the prior year, more than the pace of inflation but not the kind of increase that would’ve been expected by economists a few years ago when 5% unemployment was seen as the economy NAIRU rate, or the unemployment rate below which inflation would begin taking off.

Instead, the unemployment rate has fallen to 3.9%, the lowest in 17 years and we’re now within shouting distance of the 3.4% unemployment rate that would mark a 50-year low.

America’s employers are sitting on lots of job openings

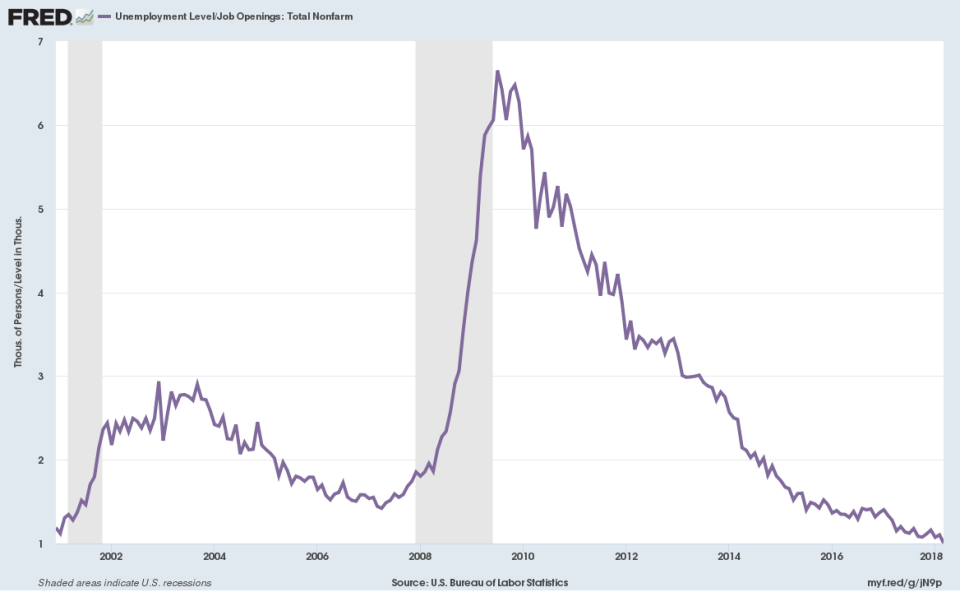

Meanwhile, data on job openings released Tuesday showed that there is currently 1 unemployed worker for each open job, while the NFIB’s latest small business optimism reading indicates that 89% of small businesses trying to hire couldn’t find qualified workers.

During the financial crisis, for instance, there were six unemployed workers for each job open. Tuesday’s job openings report also showed a record 6.55 million jobs were open during March.

Tom Porcelli, chief US economist at RBC Capital Markets, noted that in addition to a record number of jobs being unfilled right now, job openings relative to the size of the labor force broke above 4% for the first time in history.

Porcelli also notes that the Beveridge Curve, which tracks job openings relative to the unemployment rate, has indicated a skills gap during the balance of this economic expansion which this data suggests continues to persist.

“The skills gap should be corrected slowly but surely as employer needs beget training programs, etc.,” Porcelli writes. “This should lead to further significant downside on the unemployment rate.”

But with the unemployment rate already exceeding expectations about the level at which inflation would begin to really pick up and thus usher in the next recession, it seems unclear what the future of this economic expansion looks like.

Unanswered questions

Will inflation eventually rise to the level that requires the Fed act more aggressively to raise interest rates and trigger a downturn in the economy?

Or will the unemployment rate continue to fall while inflation remains low and the expansion continues through the second half of next year, thus marking it as the longest on record?

There are, of course, more than two outcomes for the economy. What happens with trade, with the midterm elections, the price of oil, and the health of corporate balance sheets amid rising interest rates will all surely play a role.

But the core relationships between inflation, the unemployment rate, and the Fed that most economists expect to hold through time are being rewritten in real time. And how it resolves is the most important economic question to be answered into the beginning of the next decade.

A version of this story was published on May 9.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland