Fed's Kashkari: There's a 67% chance we'll have another financial crisis

What are the chances we have another financial crisis in the next 100 years?

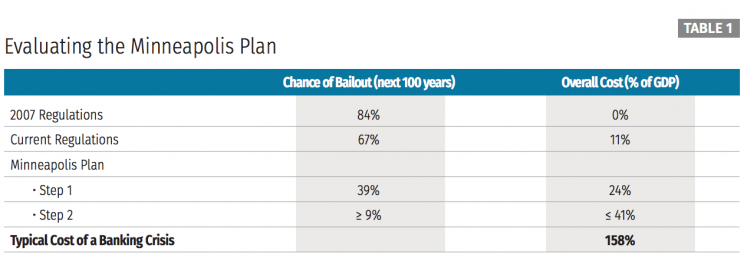

According to research out of the Minneapolis Fed, about 67%.

And Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari does not think this is low enough.

Not even close.

“Our analysis says there’s still a 67% chance we could have another financial crisis [in the next 100 years],” Kashkari told Yahoo Finance.

“Regulations have not solved that problem. We put forward a plan to put a lot more capital in the banks, make them safer, and take that risk down to below 10%. And society as a whole will be much better off if we make the banks safer and we avoid future financial crises.”

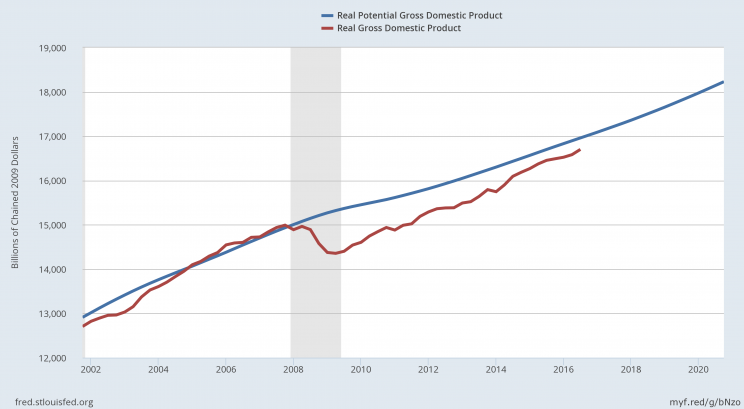

In Kashkari’s view, preventing a financial crisis is imperative given not just the impacts that event can have to the economy near-term, but the permanent damage these incidents have to economic growth.

So what does Kashkari propose doing to prevent this issue? End too big to fail banking.

Following the September 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers and the resulting seizure of global credit markets, major US and international banks have been deemed “too big to fail” given their global scope and interconectedness in the global banking sector. It is this status, in the view of Kashkari and many others, that presents the biggest risk to the economy.

“A lot of work has been done since 2008, but the biggest banks are still too big to fail,” Kashkari said. “And in my view, we need to do something about that.”

The Minneapolis Fed published a report on Wednesday outlining its plan to end too big to fail banking in the US and drastically reduce its calculated chances of a financial crisis in the US.

The basic approach is to make being a massive bank so unattractive that firms would be likely to divide into smaller units, to face less stringent capital requirements and, by extension, pose fewer risks to the broader economy.

Under the Minneapolis Fed’s proposed plan, banks with assets over $250 billion in assets will be required to meet a minimum equity requirement of 23.5% of risk-weighted assets. This means that 23.5% of the banks total asset base must be covered by stock, not bonds, issued by the bank to meet its capital needs. And this 23.5% number is for banks not deemed systemically important (in other words, too big to fail).

If you remain a large bank still deemed systemically important by the Fed, your equity requirement will increase periodically until it reaches 38%. At the end of 2015, for example, the US’ biggest banks had an equity capital ratio of around 12.3%.

Now, the Minneapolis Fed’s plan doesn’t call for the explicit breakups of big banks. But under this outline, it quickly becomes very unattractive to be a big bank.

“We want to give systemically important financial institutions the choice,” Kashkari said. “They can stay large if they have so much capital that they virtually can’t fail.”

And it is once the Fed begins to tighten the screws — or eliminate — the systemically important bans that the chances of a financial crisis, under its framework, falls to around 9%.

Kashkari compares this regulatory approach to what’s been taken in the nuclear power industry where plants are regulated to such an extent they almost can’t fail because, well, we all know a nuclear meltdown is bad. So too are financial crises.

This approach to banking regulation, Kashkari outlines, is sort of like why you wear a seatbelt: not because you expect to get in a car accident that day, but because when you’ll be better off if and when that accident happens.

As the president of a regional Fed bank, Kashkari does not have the academic credentials one might expect. Kashkari is a mechanical engineer by training — not an economic PhD — who has done stints at Goldman Sachs and PIMCO, and was most notably in charge of directing TARP (Trouble Asset Relief Program), which was put in place after the financial crisis.

It is this background, then, that informs Kashkari of what the primary task should be for the Federal Reserve.

“Simply put, our jobs are to look out for the biggest risks to the US economy,” Kashkari said.

“And our eyes are wide open. And here’s a risk that we identified and that we think we have the expertise [to address]… So this is where we’re starting, but we a got a lot more work to do.”

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance.

Read more from Myles here; follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland